Reflections on "The Insulted and Injured": Reconsidering the Gecekondu Question in 1960s Turkey

This study examines how gecekondu settlements in 1960s Turkey functioned as spatial manifestations of class struggle and redistributive mechanisms, wherein rural migrants—systematically humiliated and marginalized by state discourse—nevertheless enacted a de facto urban land reform.

As I glance back at my own work, "Ezilmiş ve Aşağılanmışlar: 1960'lar Türkiye'sinde Gecekondu Meselesi," published in Mülkiye Dergisi, I am struck by how the fundamental questions I sought to address remain persistently relevant in both Turkish urban studies and broader debates about informal urbanization processes across the Global South. What began as an archival excavation of a pivotal decade in Turkey's urban transformation has, I hope, contributed to a more nuanced understanding of how subaltern classes negotiate their place within the contested terrain of modernizing cities.

You can find the Turkish version here.

Departing from Conventional Narratives

My primary objective in undertaking this study was to challenge what had become a petrified orthodoxy within Turkish urban historiography: namely, the facile attribution of gecekondu settlements to the supposed "liberalization" of the Democratic Party period (1950-1960). This narrative—pervasive in both academic literature and popular discourse—not only misconstrues the temporal dynamics of Turkey's urbanization but, more perniciously, obscures the intrinsic relationship between industrialization, labor migration, and informal settlement formation.

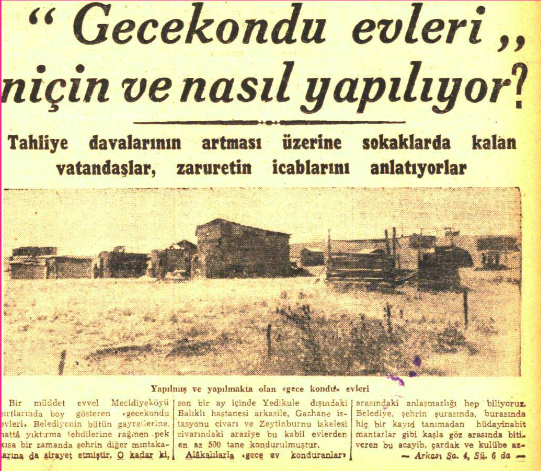

What I discovered through meticulous archival research was that the gecekondu phenomenon constituted not an aberration within Turkey's urbanization trajectory but rather its inevitable manifestation within the particular constraints of a late-industrializing, semi-peripheral political economy. As I argue in the paper, "Slums emerged alongside Turkey's industrialization and its genuine capitalist accumulation process, whether you call it monopolistic state capitalism or comprador assembly industry bourgeoisie." The fundamental causality was clear: "As labor began to concentrate in urban areas, slums appeared as a consequence."

The Epistemological Violence of Technocratic Urban Discourse

Perhaps the most viscerally affecting aspect of my research process was encountering the profound epistemological violence perpetrated against gecekondu residents through the discursive practices of state officials, urban planners, and even ostensibly progressive intellectuals. The persistent characterization of these settlements as "anomalous," "rural," and "backward" betrayed a profound unwillingness to recognize their residents' legitimate claims to urban citizenship.

I found particularly revealing the 1960 statement by Fehmi Yavuz, Minister of Development and Housing in the post-coup government, who declared: "Peasants, who can fill their free time in nearby industrial centers, will learn better living conditions and apply them in their village, thereby preventing the mass migration to our major cities." Such pronouncements—with their bizarre presumption that rural-to-urban migration stemmed from peasants' excessive "free time" rather than structural economic necessity—reveal the profound cognitive dissonance that permeated technocratic approaches to urbanization.

As I note in the paper, "Only the ideology of Turkishness could hope that this gap would be filled by supernatural means." The consistent refusal to acknowledge the material reality of migration and informal settlement—preferring instead fantastical visions of peasants voluntarily returning to their villages—constituted a fundamental evasion of the state's responsibility to provide adequate housing for its rapidly urbanizing population.

The Gecekondu as Redistributive Mechanism

What I consider perhaps the most theoretically generative aspect of my analysis is the conceptualization of gecekondu settlements as what I term a "redistributive lever" (yeniden bölüşümün manivelası). Moving beyond both romanticized and pathologizing accounts, I sought to demonstrate how these settlements functioned as mechanisms through which migrant workers effectively enacted a de facto land reform in urban areas.

The data I compiled regarding Zeytinburnu is particularly telling: of the 3,812 families who owned gecekondu homes there in the early 1960s, thousands would eventually transform their precarious dwellings into valuable assets, becoming property owners and, in many cases, rentiers. This process—whereby informal settlers gradually secured tenure rights and eventually integrated into the formal property market—demonstrates how gecekondu settlements served as "a springboard for migrants who moved to the city for industrial employment to establish a foothold in urban life."

This analysis challenges both traditional Marxist and neoliberal frameworks. Rather than viewing informal settlements as either revolutionary spaces of resistance or entrepreneurial zones of self-help, I have sought to understand them as sites of complex negotiation within the constraints of peripheral capitalism—spaces where the urban poor, through persistent political engagement and strategic adaptation, gradually secured partial inclusion in the redistributive mechanisms of urban growth.

Literary Sources as Historical Evidence

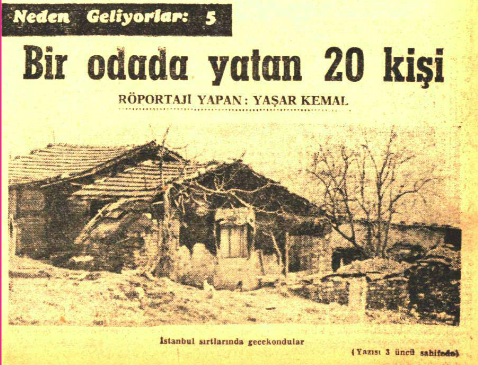

In methodological terms, one of my principal contributions has been to incorporate literary sources—particularly the works of Yaşar Kemal and Orhan Kemal—as vital repositories of social knowledge about the gecekondu experience. As I note in the paper, "In Turkey, where social sciences have historically pursued universal laws and principles rather than descriptive analysis, where the normative has always been preferred over the performative, it was perhaps inevitable that novels would come to serve as good social science, that poetry would take the place of good philosophy."

The profound sense of aşağılanmışlık (humiliation) and ezilmişlik (oppression) that characterized the migrant experience emerges vividly in these literary accounts. Consider Yaşar Kemal's poignant description of a confrontation on an Istanbul bus, where a middle-class passenger berates a group of rural migrants: "Was Istanbul ever like this? Was it ever like this, sir? In days past, men dressed like these would not even dare approach Taksim Square, let alone board a bus there."

Such literary testimonies capture dimensions of the urban experience that quantitative analyses and policy documents inevitably elide. They record the affective texture of urban marginality—the subjective experiences of discrimination, displacement, and struggle for recognition that shaped migrants' relationship to the city.

The 1970 Cholera Epidemic as Historical Inflection Point

My analysis culminates in an examination of the 1970 Sağmalcılar cholera epidemic—a catastrophic event that exposed the profound infrastructural neglect of gecekondu areas. This epidemic, which caused thousands of illnesses and dozens of deaths, represented what I characterize as the "final straw in the accumulation of oppression and humiliation."

The state's response—prioritizing the suppression of news reports over substantive public health interventions—revealed the profound contempt with which gecekondu residents were regarded. Particularly telling was Abdi İpekçi's bewilderment, expressed in a newspaper column, that these residents did not simply return to their villages in the face of such devastating conditions.

This episode marked a critical historical inflection point, after which the relative quiescence of gecekondu residents gave way to more explicit political mobilization. As I note, "After Sağmalcılar, the 1970s became years in which hope began to sprout." Drawing on Kemal Karpat's research in Sarıyer-Baltalimanı, I document how, by the late 1960s, the Workers' Party of Turkey (TİP) had begun to gain significant support in gecekondu areas—a development that would significantly alter Turkey's political landscape in the subsequent decade.

Theoretical Implications for Urban Studies

Beyond its contribution to Turkish urban historiography, I believe my work offers several broader theoretical insights for urban studies. First, it demonstrates the inadequacy of modernization theory—with its presumption of linear progression from "traditional" to "modern" forms—for understanding urbanization processes in the Global South. The gecekondu phenomenon reveals how informality constitutes not a temporary stage to be overcome but rather an enduring feature of peripheral urbanization.

Second, my analysis challenges the artificial separation of "formal" and "informal" sectors in urban economies. The gradual transformation of gecekondu areas through metalaşma (commodification)—whether through small-scale developers, direct state intervention via TOKİ (Housing Development Administration), or public-private partnerships—demonstrates the dialectical relationship between informal settlement and formal real estate development.

Finally, my work contributes to ongoing efforts to provincialize urban theory by demonstrating how Turkey's distinctive urbanization trajectory cannot be adequately understood through conceptual frameworks derived primarily from Western European or North American contexts. The gecekondu experience demands theoretical approaches attentive to the specific dynamics of peripheral capitalism, state formation, and class struggle in late-industrializing societies.

Conclusion: Urban Citizenship and the Right to the City

As contemporary Istanbul undergoes increasingly aggressive urban transformation projects—with established communities in formerly gecekondu areas like Fikirtepe and Sultanbeyli facing displacement through state-led gentrification—the historical analysis I have offered provides essential context. It reveals current developments not as novel phenomena but as the latest phase in the long-running contestation over urban space and citizenship in Turkey.

In this sense, the "insulted and injured" of the 1960s have not disappeared but rather been transformed. Their struggle for recognition and inclusion—for what Henri Lefebvre would term "the right to the city"—continues in new forms and contexts, even as their physical habitats undergo radical transformation.

If my work contributes even modestly to a more nuanced understanding of these complex processes—and to greater recognition of the agency and resilience of those who built Istanbul's gecekondu neighborhoods—I will consider it to have fulfilled its scholarly purpose.